Leek Moth in Canada

Introduction

The leek moth (or onion leafminer), Acrolepiopsis assectella Zeller, is an invasive alien species of European origin that damages Allium spp. It was first identified in Eastern Ontario in 1993. The distribution of the pest includes Asia, Africa, Europe and Canada. In 2001 and 2002, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) surveys found leek moth populations in a localized area in Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec (National Capital Region Ottawa-Carleton and l'Outaouais). In 2003, the CFIA conducted surveys in Ontario in 16 areas outside of counties where leek moth had previously been detected. This survey found a single adult in York County. In 2007, OMAFRA staff installed pheromone traps in a number of locations in Central and Southwestern Ontario. Leek moth was identified in four additional locations: Centreville, Picton, Brighton and Bowmanville. Surveys in the U.S. indicate the pest is also present in a number of U.S. states, including Hawaii.

The leek moth is considered a serious pest in some parts of Europe, with up to 40% infestation in areas where the insect has several generations per year. Where generations are limited to one-to-two per year, leek moth is sporadic and causes minor economic damage.

The leek moth is a known pest of alliums, including onion, garlic, leeks, chives, green onion, shallot, elephant garlic, wild garlic, etc. There are more than 500 species of allium worldwide with approximately 60 species (wild and cultivated) in North America.

Most literature reports that leek is the preferred host of the leek moth; however, other allium crops such as garlic and chives are also very attractive to the pest. Larvae can cause extensive damage by tunnelling mines and feeding on leaf tissue and occasionally on bulbs (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 1. Garlic damage.

Figure 2. Onion damage.

Figure 3. Garlic damage and feeding larva.

Figure 4. "Window" damage on an Onion leaf.

In garlic, larvae also attack the scape (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Entry hole with subsurface tunnelling on a garlic scape.

Figure 6. Frass and damage to garlic plant.

On alliums with flat leaves, including leeks and garlic, larvae feed on top of and inside the leaf material. They bore through folded leaves towards the centre of the plant, causing a series of pinholes on the inner leaves. Larval mines in the central leaves become longitudinal grooves in the mature plant. On leek, larvae prefer to feed on the youngest leaves but can consume leaves more than 2 months old. Leek moth larvae enter hollow leaves, such as those of onions and chives, to feed internally, creating translucent "windows" on the plant surface. Occasionally, larvae attack reproductive parts of the host plant but usually avoid the flowers, which contain saponins that inhibit insect growth. Affected plants may appear distorted and are more susceptible to plant pathogens. In general, damage is more prevalent near field perimeters.

Identification

The adult leek moth is a small, reddish-brown moth with a white triangular mark on the middle of the folded wings. It has a 12-15 mm wingspan and is 5-7 mm long with wings folded at rest. The hindwings of the moth are heavily fringed and are pale grey to light black in colour (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Adult moth at rest (side view).

Source: Jean-Francois Landry, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Eggs are iridescent white, 0.4 mm in diameter and difficult to detect (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8. Magnified leek moth eggs.

Source: Andrea Brauner, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Figure 9. Leek moth eggs on a garlic umbrel.

Larvae are yellowish-green with a pale brown head capsule and eight small grey spots on each abdominal segment (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Leek moth larva.

Source: Andrea Brauner, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

At maturity, larvae reach 13-14 mm in length. The reddish-brown pupa is encased in a loosely netted cocoon (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11. Close up of a pupa within its mesh cocoon.

Source: Andrea Brauner, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Figure 12. Pupa on a garlic leaf.

Most cocoons are found on host plants but can be located on detritus (decaying plant matter) and on neighbouring vegetation.

Life History

There are three flight periods of leek moth per season in Ontario. In Europe, the insect can overwinter as an adult moth or as a pupa in various sheltered areas such as buildings, hedges and plant debris; field data collected in Ontario and Quebec have found the same. Adults become active and emerge in the spring when temperatures reach 9.5°C and mate shortly thereafter. Eggs are laid singly on lower leaf surfaces whenever night temperatures are above 10°C-12°C. Females lay up to 100 eggs over a 3-4-week period. When eggs hatch, larvae enter leaves to mine tissues (leafminer stage). After several days, larvae move towards the centre of the plant where young leaves are formed. After several weeks of active feeding, larvae climb out onto foliage and spin their cocoons. Pupation lasts about 12 days, depending on weather conditions. Leek moth numbers and associated damage typically increase as the season progresses.

In Ontario, pheromone trap monitoring over the past 4 years has provided information on when leek moth flight periods occur. The first flight (overwintering population) appears to begin late April, ending mid-May. The second flight period (first generation) can begin as early as mid-June but may not begin until the end of June and extends, respectively, into early to mid-July. If the second flight period started early July, then the last flight (second generation) usually begins late July, ending mid-August. When the second flight period starts in mid-July, the last flight period will begin mid-August, ending in late-August.

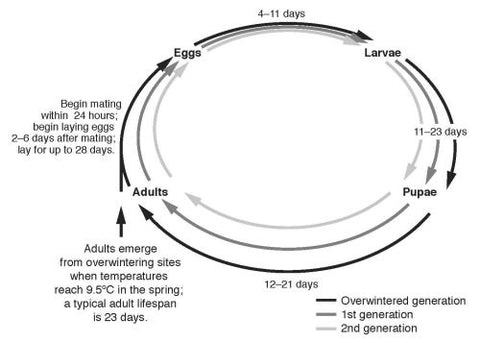

Adults emerge from overwintering sites when temperatures reach 9.5°C in the spring. Emerged adults begin mating within 24 hours and start laying eggs 2-6 days after mating. Females can lay eggs up to 28 days from first emergence. Eggs hatch within 4-11 days, depending on daily temperatures. Hatched larvae mature through five life stages between 11 and 23 days at which time they will pupate on plants, emerging as adults 12 and 21 days later.

Figure 13. Leek moth life cycle.

Monitoring and Management

Leek moth presence and activity can be monitored using commercially available pheromone trapping systems. Pheromone lures are placed in white delta or white wing traps installed around the field edge in mid-to-late April (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Leek moth pheromone trap.

In Ontario, the leek moth may be easily confused with the carrion-flower moth (Figures 15 and 16), a harmless native species present in Southern Ontario.

Figure 15. Carrion-flower moth adult.

Source: Jean-Francois Landry, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Figure 16. Leek moth adult.

Source: Jean-Francois Landry, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

It is not known whether the carrion-flower moth could be attracted to the pheromone lures set to detect the leek moth and thus confuse monitoring results. Presently, the range of the leek moth does not overlap with that of the carrion-flower moth, but when it does, it will become important to distinguish the two species. Unfortunately, this requires microscopic examination of the mating organs by a trained insect taxonomist.

Research in Ontario has found that insecticides, including organic formulations, can control leek moth populations and reduce overall damage when their applications are properly timed.

In Quebec, a decision-based model is recommended to time insecticide applications. In this system, growers examine 25 plants throughout the field and note the number of plants that exhibit damage. The threshold is 5%: if more than one plant is damaged, a spray is recommended.

In Ontario, research has consistently found that pheromone traps alone can be used to properly time insecticide applications. Insecticide applications made 7-10 days following a peak flight of leek moth adults (determined through the use of the pheromone trap system) greatly reduce the leek moth population and amount of damage it causes.

Cultural controls may be effective in reducing populations below damaging levels. Cultural controls include:

- crop rotation

- delayed planting

- removal of old and infested leaves

- destroying pupae or larvae

- early harvesting (to avoid damage by last generation larvae and population build-up)

- positioning susceptible crops away from infested areas

- destruction of plant debris following harvest

The literature suggests that most moths will not fly more than 100-200 m from overwintering sites. However, it is important to remember that wind movement may result in long-distance transportation of this pest.

Tillage/burial of debris can also help eliminate larvae and pupae that remain in the field following harvest.

German literature suggests that damage to leek may be reduced by covering leeks with netting prior to female activity and cutting off all outer leaves before the winter leaves appear in late season. Research in Ontario has consistently shown that the use of lightweight floating row covers can protect developing plants from leek moth damage (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Row covers installed over garlic rows.

Row covers can be easily removed during the day for weeding or scaping. As long as they are reassembled prior to dusk, there is little risk of leek moth entering the enclosures.

In Europe, a number of predators, parasites and pathogens are known to attack the larvae and pupae of the leek moth. Currently, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada researchers are evaluating native North American species that may offer control, as well as European biological control candidates, for release in Canada.

This Factsheet was written by Jennifer Allen, Vegetable Crop Specialist, OMAFRA, Guelph; Hannah Fraser, Entomology Program Lead, OMAFRA, Vineland; and Margaret Appleby, IPM Systems Specialist, OMAFRA, Brighton. This Factsheet was originally authored by Kristen Callow, Vegetable Crops Specialist, OMAFRA; Hannah Fraser, Entomology Program Lead, OMAFRA; and Jean-François Landry, Research Entomologist, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

© Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2015

The information on this page was written and copyrighted by the Government of Ontario. The information is offered here for educational purposes only and materials on this page are owned by the Government of Ontario and protected by Crown copyright. Unless otherwise noted materials may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes. The materials must be reproduced accurately and the reproduction must not be represented as an official version. As a general rule, information materials may be used for non-profit and personal use.